La gente de Ecuador

So, I’m finally in Ecuador, and goodness has it been a blur! I have met so many amazing people and seen some of the most uniquely beautiful landscapes. From la Sierra to el Oriente, I feel like I’ve traveled to different worlds. Upon my landing in Quito, Ecuador, Dolores (the taxi driver’s wife) was waiting to welcome me with a nice tight hug. Let me tell you, after flight delays and cancellations, and 24 hours of continuous travel, that hug was exactly what I needed. Dolores didn’t even know what I had been through, but she welcomed me with a warm smile and open arms, offering me the love and reassurance that I wanted.

Dolores and her husband, Segundo, drove me to my hotel, and during our drive, they told me so much about their country. I’ve noticed through the way that locals talk about Ecuador that many are aware and proud of the undeniable beauty of the country. Segundo was proud in his description of Ecuador, even when we talked about the unfortunate side of things. Ecuadorians don’t shy away from challenging topics, like racial divides, social representation, politics, economics, and others of that nature. You must be a critical thinker in everyday conversations.

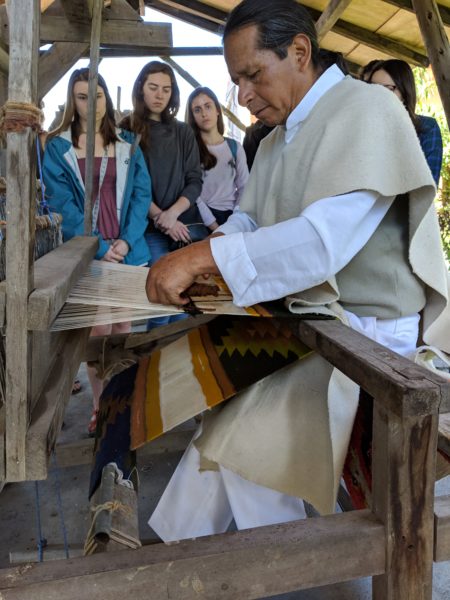

I hadn’t stepped into the classroom until my second Monday in the country, but I’d learned more in one week of traveling and meeting locals than I would’ve in a classroom. Even through simply observing the intersection of traditional and modern ways, I saw the resistance and multiculturalism that is present in Ecuador. The indigenous communities that we had the privilege to meet in Otavalo, Tena, and Salasaca emphasize what resistance by existence truly means. They open their doors to strangers and friends in hopes to share their knowledge, culture, and traditions so that it is never forgotten. In Salasaca, Anita and Francisco gave us the opportunity to use their telar, a traditional loom. Although, I personally did not try it, I understood the complexity of the practice from watching my peers struggle. This experience alone showed me how talented Francisco, like many other often-overlooked indigenous craftsmen, must be. Anita let us hilar, which, simplified, is pulling and twisting sheep’s wool from one stick to another to make a thin string. In Anita’s culture, women who can’t complete house chores, such as hilar, are referred to as “carishinas.” This is a title I’ve proudly adopted after failing to make string.

It’s impossible to travel throughout Ecuador and not respect the indigenous communities and their never-ending resistance. Their mere existence is a consistent fight to maintain their language, culture, and traditions. I don’t know if this resistance will ever end, as euro centrism, globalization, and racism continue to attempt to eradicate these nations. Today, wearing their traditional clothing and keeping their traditions is expensive. A traditional poncho takes one year to make and sells for around $1,500 (due to the mass amount of time, effort, and resources the traditional process requires). Yet $1,500 is not cheap, and this impacts how many people can actively practice their own culture. I had never even considered the impact of the economy and globalization on native nations. Regardless, these communities persist. They continue wearing their traditional clothing, using their traditional techniques, and, most importantly, welcoming visitors with a smile, a meal, some guayusa tea, and even some chicha (more on this delicious beverage later). I felt the resistance come from a place of love: a love for their upbringings, for themselves, for their communities, and for the “Pachamama”.

I can’t help but get emotional sharing this small portion of my experience because, remembering Dolores, Segundo, Anita, and Francisco, I am overwhelmed with the love that they gave me and our group. I will carry their energy and love with me throughout my time in Ecuador. I only hope that my path in life will lead me back to them and everyone else I’ve met. There is so much more I want to share and so many others that I would love to recognize, but I am left with one new word: Pakrachu – Gracias – Thank you. I share this sentiment with CEDEI and everyone else who has shared a part of their life with me in these past days.